Evolution of Indian Constitution During Crown Rule: 1858-1947

10 min read

Nov 26, 2025

Before You Read: Understand the Overview for Better Learning

Every Act passed during Crown Rule between 1858 and 1947 had three underlying objectives:

- Maintaining British control while appearing progressive – Each reform had "safeguards" preserving British power over defence, foreign affairs, and emergencies.

- Gradual, minimal expansion of Indian participation – Reluctant concessions designed to co-opt moderate Indians and delay independence.

- Divide and rule through communal representation – Separate electorates (1909 onwards) created religious divisions leading to Partition.

If you keep these three themes in mind, the logic behind every Act will become clearer and easier to remember.

For Prelims

Focus on firsts, years, names, and institutions: First Indian in Council (1861), first elections (1892), separate electorates (1909), dyarchy (1919), Federal Court (1937), RBI (1935), Morley-Minto, Montagu-Chelmsford, Mountbatten.

Memorisation of all facts is not required. Focus on major provisions and key personalities.

For Mains

Focus on themes:

- How each Act balanced British control with Indian demands

- Evolution from no representation → provincial autonomy

- Communalism as deliberate policy (1909 separate electorates → Partition)

- Federal structure (1935) as blueprint for Indian Constitution

- Constitutional continuity vs. transformation post-independence

TL;DR

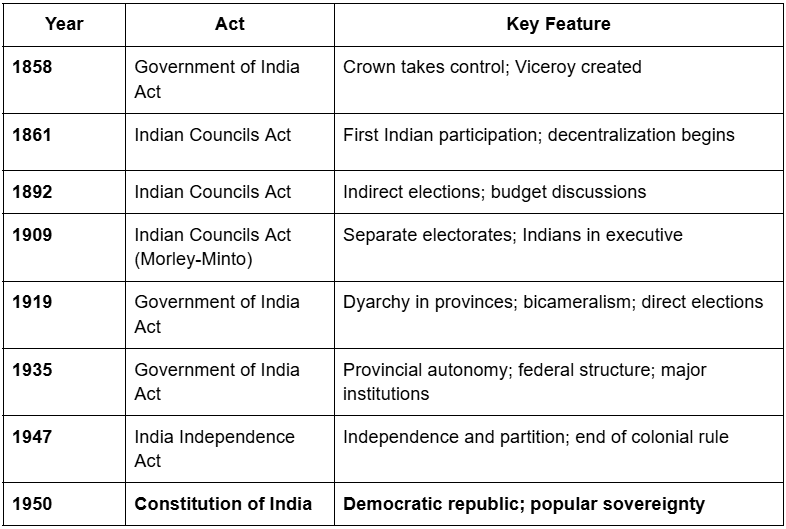

✓ 7 Acts over 89 years (1858-1947)

✓ 3 Main Objectives: Control, gradual participation, divide communities

✓ 3 Key Evolutions: No representation → Autonomy | Centralization → Federation | Nomination → Direct elections

✓ 2 Watersheds: 1909 (communal electorates) | 1935 (federal blueprint)

✓ 1 Result: Constitutional framework for independent India + Partition tragedy

The Pattern: Each Act was British response to Indian resistance. Indians turned limited concessions into platforms for demanding more—ultimately winning independence.

Introduction

Between 1858-1947, British Crown rule transformed India's governance through a series of constitutional acts. Each act was a response to Indian nationalist demands, British strategic interests, and the need to maintain colonial control while appearing progressive. This period laid the constitutional foundation for independent India.

Key Pattern: Gradual, reluctant expansion of Indian participation → From no representation (1858) to provincial autonomy (1935) to independence (1947)

1. Government of India Act, 1858

Context: Passed after 1857 Revolt to transfer power from East India Company to British Crown.

Key Provisions:

- Abolished East India Company (ended 258 years of Company rule)

- Governor-General redesignated as Viceroy (Lord Canning - first Viceroy)

- Created Secretary of State for India (British Cabinet member)

- 15-member Council of India to assist Secretary (advisory only)

- Abolished Board of Control and Court of Directors

- All Company territories, powers, and revenues transferred to Crown

Significance:

- Established direct Crown control over India (British Raj begins)

- Centralized authority: Crown → Parliament → Secretary of State → Viceroy

- Set precedent for parliamentary legislation on India

- No Indian participation - purely administrative reorganization for British control

2. Indian Councils Act, 1861

Context: British realized need for Indian cooperation post-1857; cautious liberalization to co-opt Indian elites.

Key Provisions:

- First Indian nomination to Viceroy's Legislative Council (non-official, advisory only)

1862: Raja of Benares, Maharaja of Patiala, Sir Dinkar Rao nominated

- Restored legislative powers to Bombay and Madras Presidencies (reversed centralization)

- New legislative councils created for Bengal, NWFP, and Punjab

- Portfolio System recognized (introduced by Lord Canning 1859) - each council member handled specific departments

- Viceroy's ordinance power during emergencies (6 months validity)

Significance:

- Principle of Association: First acknowledgment that Indians should have some legislative role

- Decentralization begins: Provincial councils for local matters

- Created class of Indians experienced in legislative procedures

- Purely advisory role - real power remained with British

3. Indian Councils Act, 1892

Context: Indian National Congress formed (1885); rising demand for representation; British response with minimal reforms.

Key Provisions:

- Increased non-official members in Central and Provincial councils

- Enhanced functions:

Right to discuss annual budget (but no voting power)

Right to ask questions to government (6 days notice required) - Indirect elections introduced:

Universities, district boards, municipalities recommended members

Chambers of commerce, zamindars represented

Limited and indirect, but established elective principle

Significance:

- Democratic foothold: Election principle introduced (though indirect)

- Financial accountability: Budget discussions and questions created oversight mechanism

- Congress victory: Validated moderate constitutional approach

- Communal seeds: Class/interest-based representation encouraged sectional loyalties

- Real power still with British: members had no authority to reject legislation

4. Indian Councils Act, 1909 (Morley-Minto Reforms)

Context: Post-1905 Bengal Partition protests; rising extremism in Congress; Muslim League formed (1906); British strategy to appease moderates and divide communities.

Key Provisions:

- Substantially increased council sizes:

Central Legislative Council: 16 → 60 members

Provincial councils also expanded significantly - Enhanced powers:

Discuss matters of public interest

Move resolutions

Ask supplementary questions

Debate budget (but no voting power on whole budget) - Indians in Executive Council (first time):

Satyendra Prasad Sinha: First Indian member of Viceroy's Executive Council (1909) - Separate electorates for Muslims:

Muslim voters elect Muslim representatives

Extended to Sikhs, Christians, Anglo-Indians, Europeans later - Separate representation for: Universities, chambers of commerce, zamindars, presidency corporations

Significance:

- Executive breakthrough: Indians could now influence policy implementation

- Expanded political participation: More Indians in legislative forums

- Communal poison: Separate electorates legalized communalism

Lord Minto known as "Father of Communal Electorate"

Led to Hindu-Muslim political division

Set path toward eventual Partition - Divide and rule: Morley stated reforms not meant for parliamentary system but to strengthen British rule

5. Government of India Act, 1919 (Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms)

Context: WWI (1914-18) - India's massive contribution; Montagu Declaration (August 1917) promised "progressive realization of responsible government"; However, also Rowlatt Act (1919) and Jallianwala Bagh massacre created atmosphere of hope and betrayal.

Key Provisions:

Provincial Level:

- Dyarchy introduced: Dual government in provinces

Reserved subjects: Law & order, finance, revenue (British Governor + Executive Council)

Transferred subjects: Education, health, local govt, agriculture, public works (Indian Ministers responsible to legislature) - Provinces separated from centre (distinct subjects and budgets)

Central Level:

- Bicameralism introduced (first time):

Legislative Assembly (Lower House): 145 members, 3-year term

Council of State (Upper House): 60 members, 5-year term - Majority elected members

Other Provisions:

- Direct elections introduced (limited franchise - ~10% of adult males)

- Voting based on property, tax, or education

- 3 of 6 members of Viceroy's Executive Council to be Indians

- Separate electorates extended to Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians, Europeans

- Public Service Commission established

- Statutory Commission provision (Simon Commission 1927 was result)

Significance:

- Responsible government experiment: Dyarchy = training ground for parliamentary democracy

- Provincial autonomy begins: Separate spheres for central/provincial matters (crucial for federal India)

- Bicameralism: Foundation for modern Parliament (Lok Sabha/Rajya Sabha model)

- Critical flaws:

Dyarchy unworkable: Ministers controlling education/health had no power over finance/police

Centre unchanged: Full British control at central level

Limited franchise: 90% Indians excluded

Deepened communalism: More separate electorates - Congress rejected; Gandhi launched Non-Cooperation Movement

- Despite flaws, established principles used in 1935 Act and Indian Constitution

6. Government of India Act, 1935

Context: Civil Disobedience Movement (1930-34); Round Table Conferences (1930-32); Simon Commission (1928); MacDonald's Communal Award (1932); Poona Pact (1932). Britain's most comprehensive constitutional reform - longest Act by British Parliament (320 sections, 10 schedules).

Key Provisions:

Federal Structure (never implemented):

- All-India Federation of British provinces + princely states (voluntary)

- Failed: Princely states refused to join

Division of Powers:

- Three Lists:

Federal List: 59 subjects (defence, foreign affairs, communications)

Provincial List: 54 subjects (health, education, local govt)

Concurrent List: 36 subjects (criminal law, marriage, contracts)

- Residuary powers: With Viceroy

- Direct influence on Indian Constitution's Seventh Schedule

Provincial Autonomy (implemented 1937-39):

- Dyarchy abolished in provinces

- Full responsible government

- Governors became constitutional heads (advised by ministers responsible to legislature)

- Significant autonomy in administration and finance

- Governors retained "special powers"

Dyarchy at Centre (never implemented):

- Reserved subjects: Defence, foreign affairs (Governor-General)

- Transferred subjects: Other matters (ministers)

Electoral Expansion:

- Franchise extended to ~30 million (10-12% of population)

- Women could vote (with qualifications)

Institutional Establishment:

- Federal Court (1937) - precursor to Supreme Court

- Reserve Bank of India (1935) - central bank

- Federal & Provincial Public Service Commissions

Communal Representation:

- Continued separate electorates

- Extended to Scheduled Castes (MacDonald's Communal Award)

Special Powers:

- Governor-General/Governors could override legislatures

- Emergency provisions

- Protection for British business interests

Significance:

Major Contributions:

- Federal blueprint: Three-list system directly adopted in Indian Constitution

- Provincial autonomy success: Congress ministries (1937-39) proved Indians could govern effectively

- Institutional framework: Federal Court, RBI, PSCs provided continuity post-independence

- Legal continuity: Served as interim constitution (1947-50) with modifications

Critical Limitations:

- Colonial document with numerous "safeguards" for British control

- Federation never materialized (princely states didn't join)

- Communal politics deepened

- Lacked popular legitimacy (imposed by British Parliament, not created by Indians)

Congress Response: Rejected as "totally unacceptable" but contested 1937 elections pragmatically; All ministries resigned 1939 when Viceroy unilaterally declared war.

Constitutional Legacy: Indian Constitution retained federal structure, three lists, administrative provisions, but transformed them with popular sovereignty, fundamental rights, and complete responsible government.

7. India Independence Act, 1947

Context: Post-WWII Britain exhausted; INA trials, RIN mutiny (1946), nationwide upheaval; Muslim League's Pakistan demand (1940); Direct Action Day (1946); Cabinet Mission failure (1946); Mountbatten became Viceroy (March 1947) with mandate to transfer power by June 1948; Hastened to August 15, 1947.

Key Provisions:

- End of British rule: August 15, 1947

- Partition: Creation of two independent dominions - India and Pakistan

Boundary commissions (Radcliffe) to demarcate borders

- Constituent Assembly powers:

Frame and adopt any constitution

Function as legislatures until new constitutions adopted

Repeal or amend any British Act

- Interim governance: Government of India Act 1935 (with modifications) until new constitutions framed

- Governor-General: Constitutional head (acting on advice of ministers)

Lord Mountbatten: India's first Governor-General

Muhammad Ali Jinnah: Pakistan's Governor-General

- Abolitions:

Office of Viceroy

Secretary of State for India

Council of India - Lapse of paramountcy: British control over 562 princely states ended

States free to join India or Pakistan

Led to integration challenges (Sardar Patel's diplomatic work)

- Complete sovereignty: Both dominions fully sovereign, no British conditions

Significance:

Liberation:

- End of ~190 years of Company + Crown rule

- Constituent power: Indians empowered to frame any constitution without conditions

- Legal continuity: 1935 Act as interim constitution prevented chaos

- International recognition as sovereign nations

Trauma:

- Partition catastrophe:

1-2 million deaths in communal riots

10-15 million displaced

Families torn apart, lasting psychological trauma

Created hostile neighbor, permanent tension - Princely states crisis: 562 independent states required integration (Junagadh, Hyderabad, Kashmir)

- Hasty timeline: Inadequate preparation, poorly drawn boundaries, insufficient security

Constitutional Impact:

- Imposed no conditions on India's constitutional future

- Allowed Constituent Assembly 3 years to carefully draft Constitution

- Created opportunity for thorough debate and original document

- Constitution (1950) replaced all colonial vestiges with new order based on justice, liberty, equality, fraternity

Evolutionary Patterns (1858-1947)

1. Gradual Expansion of Representation:

- 1861: Nomination → 1892: Indirect elections → 1909: Communal representation → 1919: Direct elections (limited) → 1935: Extended franchise (30 million)

- Each step created political consciousness and demands for more

2. Progressive Decentralization:

- 1861: Provincial legislative powers restored → 1919: Separation of central/provincial subjects → 1935: Full provincial autonomy

- Recognized India's diversity, prepared ground for federalism

3. Advisory to Responsible Government:

- 1861: Discuss only → 1892: Question and discuss budget → 1909: Move resolutions → 1919: Dyarchy (some responsible subjects) → 1935: Full provincial responsibility

- Trained Indian leaders in governance

4. Institutional Building:

- Supreme Court (1861) → Federal Court (1937) → Supreme Court (1950)

- Executive Council → Council of Ministers → Cabinet system

- Legislative councils → Bicameral legislatures → Modern Parliament

Constitutional Legacy: From Colonial to Democratic

What Indian Constitution Inherited from Colonial Acts:

From 1935 Act:

- Federal structure with three lists (Federal, State, Concurrent)

- Emergency provisions (democratized)

- Governor's role (transformed to constitutional head)

- Administrative and legislative frameworks

- Financial provisions

From Councils Acts:

- Parliamentary procedures

- Collective responsibility principles

- Legislative practices and conventions

What Indian Constitution Added:

- Popular sovereignty: "We, the People" (not Crown)

- Fundamental Rights: From US Constitution (not in British Acts)

- Directive Principles: From Irish Constitution

- Universal adult suffrage: No property/education qualifications

- Elimination of communal electorates: Single unified electorate

- Complete responsible government: No reserved powers

- Social justice provisions: Land reforms, abolition of untouchability

Key Lessons

- Representation Matters: The entire colonial period demonstrates how struggle for representation drives political evolution.

- Communalism's Danger: Separate electorates (1909) → communal politics → Partition (1947). Identity-based politics remains dangerous.

- Federalism is Strength: Centralization (pre-1861) to provincial autonomy (1935) showed diversity requires decentralization.

- Institutions Outlast Regimes: Courts, bureaucracy, legislatures survived regime change by serving functional purposes.

- Tactical Pragmatism: Congress rejected Acts (1919, 1935) but worked within them - tactical engagement over pure opposition.

- Hasty Decisions Cause Suffering: Rushed partition caused immense tragedy; major changes require careful preparation.

Conclusion

The period 1858-1947 saw India evolve from having no representation to achieving independence. Each British Act, though designed to maintain control, became a stepping stone to freedom. Indians transformed limited concessions into platforms for demanding more.

The Constitutional Journey:

- 1858: Crown control, no Indian participation

- 1861-1892: Nomination → indirect elections

- 1909: Separate electorates + executive participation

- 1919: Dyarchy + bicameralism + direct elections

- 1935: Provincial autonomy + federal structure

- 1947: Complete sovereignty

When the Constituent Assembly drafted India's Constitution (1946-49), members brought:

- Experience from colonial legislatures

- Understanding of federal structures (1935 Act)

- Knowledge of what worked and what didn't

- Hard lessons about communalism

- Confidence in Indian capacity to govern

The Final Transformation: India's Constitution (January 26, 1950) was both continuation and repudiation. It continued administrative and legal structures while rejecting colonial values. It borrowed from 1935 Act while transforming provisions with democratic spirit.

From subjugation to sovereignty - this is the story of how gradual reforms ultimately gave way to revolution, and how a subject people became sovereign citizens.

Timeline Summary

Two Critical Patterns to Track

Pattern 1: Response to Resistance

- 1858 → Response to 1857 Revolt (take direct control)

- 1861 → Response to need for Indian cooperation (minimal inclusion)

- 1892 → Response to Congress formation (indirect elections)

- 1909 → Response to extremism & partition of Bengal (divide communities)

- 1919 → Response to WWI contribution (dyarchy experiment)

- 1935 → Response to Civil Disobedience (provincial autonomy)

- 1947 → Response to post-WWII reality (forced exit)

Pattern 2: Centralization → Decentralization → Federation

- 1858: Complete centralization under Crown

- 1861: Provincial councils restored (reversal)

- 1919: Separation of central/provincial subjects

- 1935: Full provincial autonomy + federal structure

- 1947: Two sovereign nations

For Prelims: Quick Facts

✓ Years and names of Acts

✓ Firsts: First Indian in Council (1861), first elections (1892), first executive member (1909), first dyarchy (1919), first Federal Court (1937)

✓ Key personalities: Lord Canning (first Viceroy), Morley-Minto, Montagu-Chelmsford, Mountbatten

✓ Institutional creations: Federal Court (1937), RBI (1935), bicameralism (1919)

✓ Separate electorates: When introduced (1909), who called "Father of Communal Electorate" (Lord Minto)

✓ Constitutional terms: Dyarchy, provincial autonomy, three lists, paramountcy

Memorization tip: You don't need to remember all 320 sections of the 1935 Act—focus on the major provisions and their constitutional legacy.

For Mains: Key Themes

Theme 1: Colonial Control vs. Indian Demands

- How each Act balanced British interests with Indian aspirations

- Why reforms always came with "safeguards" and emergency powers

- The gap between proclaimed objectives (1917 Montagu Declaration) and actual provisions

Theme 2: Evolution of Representation

- Journey from nomination → indirect election → direct election

- Expansion of franchise (but always limited)

- From advisory to legislative to executive participation

Theme 3: Communalism as Policy

- Separate electorates (1909) as deliberate divide-and-rule

- How electoral engineering deepened Hindu-Muslim division

- Direct line from Morley-Minto Reforms → Partition

Theme 4: Federal Structure

- Why Britain moved from centralization to provincial autonomy

- Three-list system (1935) and its adoption in Indian Constitution

- Success of provincial autonomy (Congress ministries 1937-39)

Theme 5: Constitutional Continuity

- What independent India inherited from 1935 Act

- What was transformed (emergency provisions, governor's role)

- What was rejected (communal electorates, reserved powers)